In your life, you meet people. Some you never think about again. Some, you wonder what happened to them. There are some that you wonder if they ever think about you. And then there are some you wish you never had to think about again. But you do.

There are many types or personalities out there; there are therapists who are creative and fluid… and then there are the ones who need a structure and a method… A protocol offers “certitudes” and “safety” for some, but regardless of the personality style, a framework is needed. Below I will show you the protocol of the positive psychotherapy – the way it was taught to me – but it can very well serve as a model for any school of psychotherapy. Also, this article is probably the last focusing on this particular school of thought, as I will diverge in several styles of doing therapy in future articles, hence going integrative.

Psychotherapy, as any interaction with someone in this life, follows a simple pattern:

Hello! – How are you? – Goodbye!

This 3-step structure is followed during the entire psychotherapy contract but also in each and every session: you open the “scene” or the interaction (you establish the initial contact), then you deal with the client’s problem, and then you “close” the scene or “lower the curtain” or bring to a conclusion the session (or the entire therapy process, as this protocol serves both as a model for a session and for the entire therapeutic journey), so that the client does not go away from you bewildered and possibly being prone to an accident or to suicidal thoughts. The therapy sessions are separated, typically, by several days or weeks; you need to be aware that therapy functions also between sessions, when the client ponders or ruminates about what has been discussed. Often, the most important decisions and change itself happen between therapy sessions; what you typically get during a session are “a-ha moments”, when the client is struck by sudden bursts of awareness regarding a given situation. By consequence, resist the client’s urge to do very frequent sessions, as (s)he needs time to reflect on what has been discussed.

Done correctly, psychotherapy needs a written file for each client, where you write what (s)he said and your own reflections and strategies. This paper is highly confidential. And much needed if you have trouble remembering the details. In a structured therapy setting, this can be the proof you’re actually doing something with a given client (beyond the bla-bla-bla uninformed people imagine you do while in therapy) and this paper can also prove valuable when you enter supervision for a particular client and you need to tell your supervisor (and colleagues, if any) the history of that client and what have you done until that particular moment in time.

1. Hello!

This is the period when you develop an attachment with the client and when you gather information about him/her. It is also the right moment to distance yourself emotionally from the client, in the sense that you distance yourself from your own (traumatic) emotions, so as to be able to keep a clear mind facing the client’s issues.

Why you need attachment? Because, for instance, you can’t say to a client, from session number 1, that his father doesn’t love him and his mother is a whore, and hope that that client will return for session number 2 (unless they’re masochistic or they became interested in other things). Some therapists tend to be excessively sincere and direct, especially when they deal with really unaware (read defensive) clients and they are plagued by time-pressure, risking to become harmful in their bluntness. Remember the mantra: “Too much sincerity/honesty/authenticity can sometimes mean cruelty”.

Why you need to gather information? Because, for obvious reasons, you need to know what are you (both) talking about. Clients typically keep secrets… and they keep them well. It is not unusual to discover, months into therapy, that the client had one or even two secret lovers, and this will drive you mad because you worked hard thinking that you understand the situation. Assume a mantra taken from House MD, the movie: “Everybody lies”. By consequence, take the anamnesis (history) diligently, begin with name, age, family life, childhood, education, finances, job(s), drugs being used (now or in the past), alcohol, treatments (including psychiatric ones), past or present diseases or disorders, etc., and include details about previous therapy sessions with other psychotherapists (the client might get false ideas from previous therapy interventions or might already have a good psychotherapy vocabulary that may – or may not – facilitate your work). Ask also about who sent the client to you (who recommended you), about how much time the client waited so as to see you (gives a clue about the degree of motivation, given the fact that the client comes to you after a lengthy period when he/she sought a solution for his/her problems and couldn’t find one) and about his/her expectations regarding therapy (gives you an idea about his/her phantasms regarding psychotherapy). This phase is suitable for asking yourself if the client is psychotic or not, if the client is dangerous or not, if the client needs to see a psychiatrist first or not. It is your responsibility to refer the patient to a psychiatrist if you feel that something is wrong with the client, a responsibility you also have versus yourself, so as to avoid doing harm or be aggressed, respectively. You need to decide if the client can or can’t do psychotherapy; the following disorders should be avoided or managed in hyper-specialized centers, so know your limits!

- Delusional disorders & schizophrenic disorders in general

- Severe depression

- Mental retardation

- Dementia & any disorders leading to confusion/delirium

- Any disorder in the acute phase (bipolar, alcohol or drug intoxication, etc.).

Perhaps the most logical question you can ask the patient during this first period is:

What brings you here, to me? Or, what’s the problem?

This is an essential question and the client will choose a path and exhibit a particular reaction.

If the client speaks, (s)he will say something that constitutes the “spontaneous declaration of the client”. This statement is highly symbolic and informative for the trained eye, because, as Eric Berne said, what you say after you say hello reveals a lot about your position in life, about your attitude versus the others/the world and it is often the beginning of a pathological game. Also, it’s a good idea to let the client speak freely, so that you can understand how the client thinks and get a first glimpse of his/her values and life-principles (involving the meta-communication level, that is, what is conveyed indirectly about him/her-self).

If the client doesn’t speak, you need to facilitate the dialogue. So you begin by explaining that there are 2 main types of problem: physical (sensations, pain, etc.) and psychological (restlessness, anxiety, various emotions, etc.). Often, the client will answer this time. If the problem is physical, the client must identify the place of the pain/sensation in his body, and from here a dialogue can emerge. If the problem is emotional (the client is able to identify emotions), it is even easier to initiate a dialogue.

2. How are you?

This period deals with the main discussion/therapy time, and a couple of suggestions have already been given in the previous articles. In positive psychotherapy, this involves the inventory of the client’s capacities and using the balance model and possibly the concept of positum. If a conflict is identified, a negotiation between the client’s capacities is required. If the conflict is with another person, that person is also described using her own capacities and then we start to analyze the dynamic between the client and that other person, taking in consideration the different constellations of capacities. In other schools of therapy, this period is dedicated to their respective techniques: existentialistic or psychoanalytical dialogue, psychodrama (role-play), hypnosis, various cognitive-behavioral techniques, relaxation, visualization, paradoxical interventions, narrative therapy, etc. – the sky is the limit.

One important aspect at the beginning of this period is to choose a conflict on which the client desires to work. If there is no conflict (the client does not seem to see the situation from this perspective), than the client chooses a “problem” (in fact, if there is no conflict, the client does not come to therapy). Often, there are several problems to choose from; so, which one to choose? If the client knows it, it’s easy. If the client doesn’t know it, we must choose for him/her, and it depends on our skill to do this (but we basically begin with “the elephant in the room”). Following this, we establish an objective (a therapeutic objective). Defining an objective is one of the hardest things in psychotherapy and every therapist has had problems with this. But it is essential, because if you don’t know the objective, you don’t know where you’re going with the client and you’re wasting their time. Often the client has an objective (or several) and you also can have your own objectives (intermediary objectives, steps or “check points” you need to get to so as to achieve the main objective). Your objectives may not be known by the client, but you need to be very aware of them.

What constitutes an objective? Changing reality or events can never be an objective. Changing the emotions and consecutively, the thoughts/sensations/behaviors are the true objectives. In other words, changing the client’s partner’s behavior cannot be an objective, getting a good job cannot be an objective, helping someone to get divorced or leave an abusive relationship cannot be an objective. By contrast, finding love anew in the couple, finding renewed courage and passion to apply for a new job, accepting and assuming an abusive relationship or, why not, finding enough self-responsibility, self-respect, and ultimately self-love so as to be able to leave the nasty relationship – these could be objectives.

There is a lot of anxiety about this period: how to start? What has proven effective in my practice as both psychiatrist and psychotherapist was to begin by establishing with the client what stays in his/her power and what does not – the personal limits. This first move will demarcate clearly the limit between what the client can control and what is not within his/her reach. What the others do, what the others say, what the others believe, how the others judge the client – all these – are not in the realm of the client’s power – and must be acknowledged as such. This is part from a bigger process of setting up expectations. This technique works well with a lot of people, provided you know yourself what are the limits of the power of a human being (which definitely require some form of training in existentialism).

Also, during this period but also during the first and the last ones, pay a lot of attention to what is called the (emotional) transfer. When 2 human beings interact, they exchange not only ideas and words in a dialogue, but also emotional states. You will feel something about your client and you need to ask yourself what you feel and why you feel it. If you like the client or you find him/her interesting, ask yourself why! If you hate him/her, do the same! If the client is confusing you, ask yourself why the client has access to you and is able to confuse you! If you feel like crying (because the client has such a sad life-story) and you can’t take it anymore, excuse yourself and go hide yourself in the toilet (WC) and cry (the client does not need to see you and your lack of restraint)! If you feel bored, ask yourself why the client is boring for you! If you feel nothing, ask yourself why you feel nothing while interacting with another human being! Analyzing your transfer (and if what you feel comes from you or from the client) is an ongoing process, it must be permanent, as it is a great tool if you know how to use it.

3. Goodbye!

This is the period of detachment. If this period is part of a first session, it consists often in stating some sort of diagnosis or defining the problem at the level of the client’s understanding. You have the moral obligation to inform the client if the therapy can be useful in his/her case or not, if it is possible (if there is not a contraindication) and… if the therapy is necessary (the client might not need therapy, for instance, in the case in which the client has a life situation that does not involve a conflict, being already capable to deal with that issue). You also have the moral obligation to evaluate the suicidal risk and act accordingly. Another important aspect is evaluating the degree of urgency of therapy, that is, when you must see again the client and if the client can call you at the phone before the next meeting, in case of emergency.

If therapy is to continue in a second session, you must establish the objectives of therapy (the client’s objective and your intermediary and hidden objectives for the client) and you also need to ask yourself if you can do it, if you can assist the client during his/her journey. For example, if yourself got separated from your partner and the client has a similar problem, you might want to refer the client to another therapist, while explaining to the client the reason; same for a bereavement problem when you yourself have lost a loved one and you are in grief as well. Knowing your limits is essential; you are a human being, not a machine, and if you think the contrary, maybe you need to (re)enter supervision.

Along the defining of objectives, you might need to begin to think about strategies and techniques. And you might want to communicate some sort of prognosis to the client (what you think you can achieve with him/her, what you doubt, etc.). Also, it is fair to communicate the investment with therapy, the amount of money the client might give to you (psychotherapy is typically expensive, or it should be this way, as it involves hyper-specialization and time/energy investment from your part).

At the end of a session, and also as the end of therapy, many therapists need to ask their clients what they take with them from that time spent together. “What you enjoyed in the session? What will you remember from our discussion?” – these are typical questions. While replying, the client is forced to summarize and you get what is called a feedback; this helps you to get a glimpse about what the client thinks or experiences. Also, towards the end of therapy, a good idea is to expand what has been learned during therapy (the conclusions, the decisions being taken) to other areas of the client’s life, as therapy typically deals with patterns and the conflicts are between capacities and values which can be met, again and again, in various other life situations.

At the end of therapy – if you ever make it to this point and the client does not leave in the meantime, which is very frequent – after you get your last feedback from the client and hopefully the client is pleased, there is one last thing that you need to do alone: as a therapist, you write a letter to the client, stating what you would have liked to tell him/her but you didn’t, knowing that you will never encounter the client again and you will never know about his/her whereabouts. This letter will never reach the client; this letter contains your own projections and transfer, and it is deeply personal for you. The client comes to do his/her own therapy, not to enable you to do your own therapy (if it is so, you should (re) enter supervision or start therapy yourself from the position of a client). But when all is over, this final never-to-be-sent letter, will enrich you with insights about the therapeutic process and about how the client also, in his/her turn, has changed you.

We meet ourselves, time and again, in a thousand disguises, on the path of life.

—

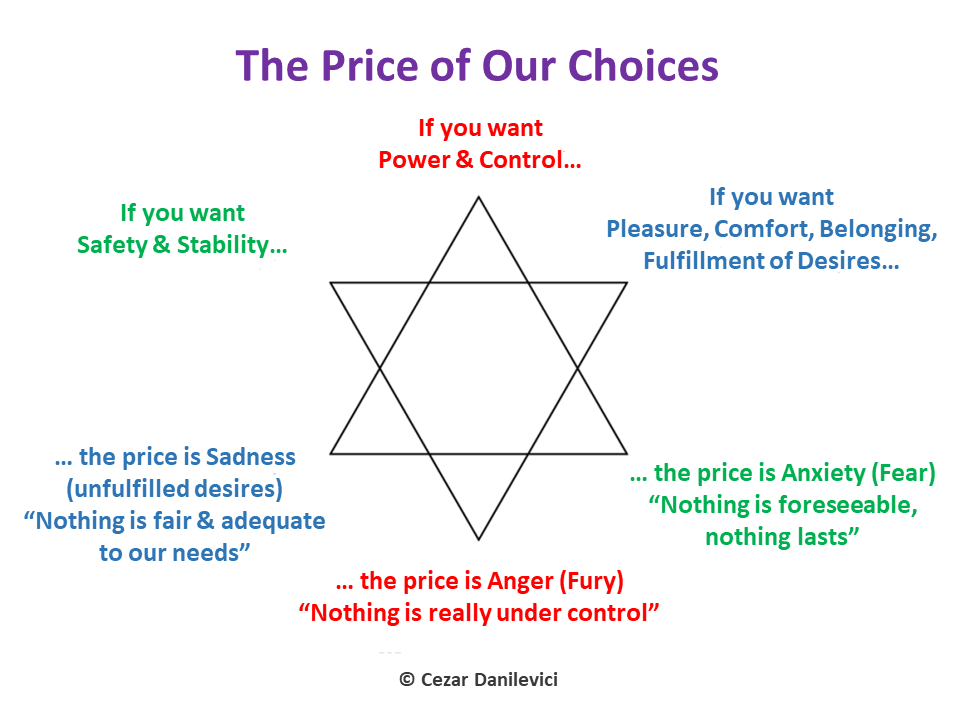

Related Infographic: