The fiercest battle is with yourself; you’re in both camps.

Moving from the idea of positum, the other innovation, or perhaps characteristic, of the positive psychotherapy method is the balance model. Each therapy school needs some theoretical scheme, some structure, because otherwise the interactions with the clients would be something like a Socratic dialogue (the best version) or a complete nonsense (the worst version). Then, when in supervision, the trainee will have to stick to something more or less structured so as not to lose him/herself in details and become confused. But then, it depends a good deal on the talent of the trainer and less on the formal doctrine; however, so as to communicate among professionals, the balance model is needed.

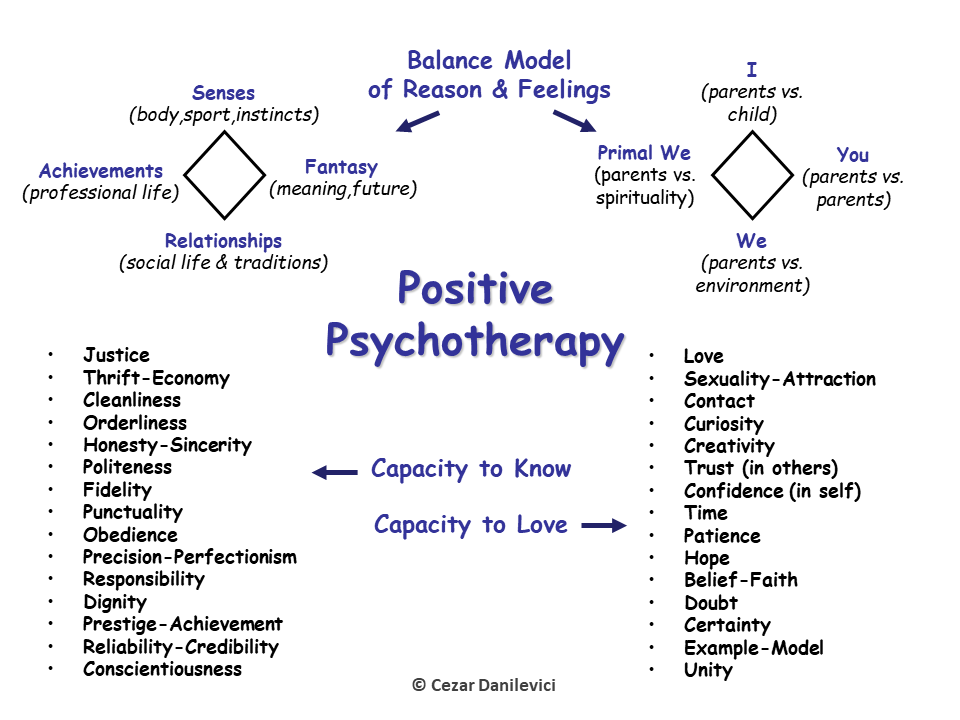

You probably never heard about the balance model if you never heard about positum. I shall leave below a link to two slides I made some time ago, for those who really need structure and are not afraid of dry theory. But for the rest, I will explain as simple as possible.

cezardanilevici.wordpress.com/positive-psychotherapy

At the heart of the positive therapy is the idea that people need balance or equilibrium in their life. This model is like a safety net connected in 4 corners; these corners are the 1. the physical body (the senses, sexuality), 2. the achievements (mostly professional (career, job) or social (marriage, social status) ones), 3. the relationships (partner, family & friends) and 4. the philosophical or spiritual life (referring mostly to mentalities, future hopes and phantasy). In a way, it is rather logical that the body, the relational, the professional and the spiritual aspects are important, and this model simplifies things enough so as to facilitate working with them. And just like in the case of a safety net, it can catch you if needed be, if it’s connected in 4 or 3 corners, but it becomes a matter of chance if your safety net has become a life line connected in 2 corners, and it is a catastrophe if you only have one corner left.

What is the practicality of this model? Well, if you have, for instance, a client who is depressed and suicidal (no fantasy about the future, no hope, no corner number 4), then it would be a bad idea to encourage him to isolate from his family and friends (corner 3), or resign from his job (corner 2) or hide in his house and avoid sport or other types of sensorial stimulation (corner 1). The balance model helps me to evaluate the gravity of someone’s situation and also tells me where I need to work with that particular client. For instance, if he is too focused on the professional aspects and overlooks/skips/ignores his body or his friends/family, I might deal with a tendency of “flight/escape into work/profession”, so the decent decision is to pull him from that corner (number 2) and suggest a redistribution of his energy and time in the other corners, so as to consolidate his safety net in case something bad happens in the future.

This balance model is a superficial or early model, especially used in counselling and by younger trainees, and offers a good structure to organize their sessions of psychotherapy. It basically means you have to discuss the 4 corners and do what you can so as to strengthen them harmoniously. And that’s it. But going deeper, especially when you can’t understand why the client doesn’t seem to change, you arrive at the emotional level. The first balance model is called the rational model because it forms the bases for typical rational discussions. There is however the deeper feelings balance model, useful when you hear from your client statements like this: “I want to change and do something different but I don’t know why I can’t”. This kind of statement shows you that the client doesn’t know rationally why he fails to do something, and this might be because there is an emotional reason for his behavior/inability to change.

The second balance model is based on what the positive therapy calls capacities or abilities. Human beings have 2 fundamental abilities according to this school of thought: the capacity to know and the capacity to love. All the other capacities emerge from these 2 fundamental ones. You can see them following the link I gave above, arranged in 2 columns, but they are quite known as values or life principles. For instance, justice, fidelity, perfectionism, sincerity, politeness, curiosity, creativity, hope or faith are among these capacities. Our inner structure is a unique constellation created by these abilities, who are often organized hierarchically, but are also “quarrelling” if we have an inner conflict. The fight or debate between 2 or more capacities is at the basis of a typical therapy session, when the client comes with a problem (s)he couldn’t solve and we are supposed, as therapists, to play the referee and explore the options with the client. Probably the typical conflict is between politeness and sincerity (“How can I tell you politely to go to hell and avoid the consequences of my sincerity?”).

In itself, a discussion based on the conflict between 2 capacities can fill well a session of therapy, with the condition that the therapist is able to correctly identify the 2 capacities. This involves an ability of analysis and synthesis (you analyze the material, that is, the chaotic discourse/monologue of the client, and then you synthetize the main ideas). For this you need to be intelligent and intuitive, because picking up the main ideas from an unstructured material is not easy. You basically do something called clarification and exploring the options, but in order to do this you need to be yourself pretty well structured and aware of your own biases. This is why in my training we spent 2 years in self-discovery, self-knowledge and self-awareness, so as to become at least aware of, if not heal, our own psychological issues.

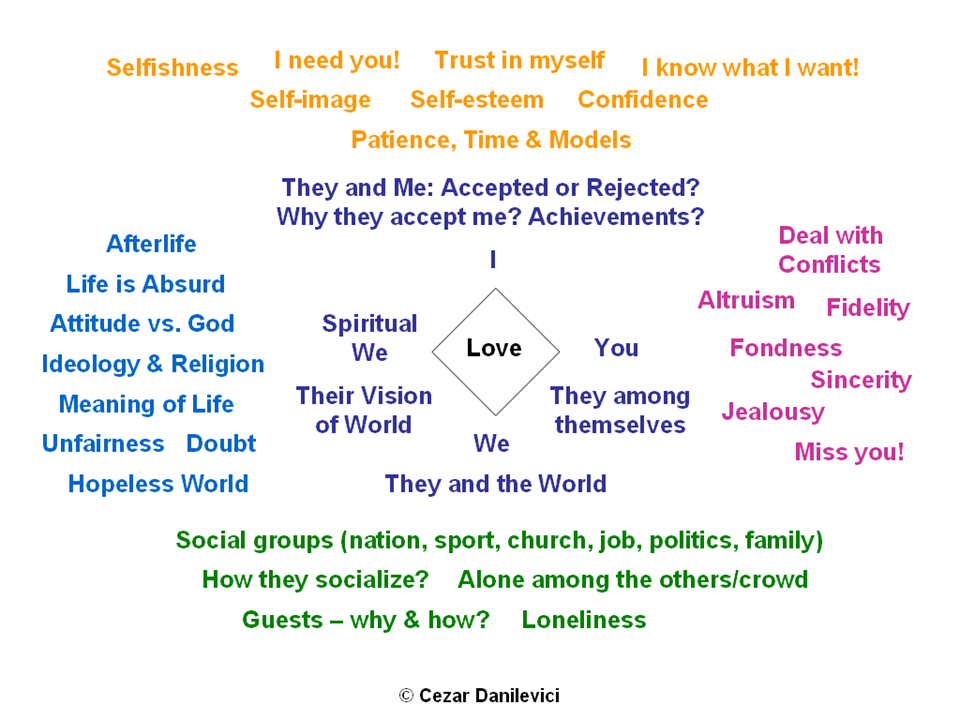

The third and deepest level of the balance model deals with a new structure made of 4 corners and, just like the capacities, resembles a lot to the existentialist techniques. If the discussion of capacities resembles the negotiation of one’s hierarchy of existential values, the inner emotional model resembles to those existential questions about “Who am I”, “Who are You”, “What is this World” and “Who are we as a Spiritual Community”. We live through learned models and patterns. Who we are is defined by how our parents saw us and what/who they told us we are. For instance, if my parents told me I am an idiot or a failure, I will eventually believe it and self-identify as such for the rest of my life. On the other hand, if the parents (or other parental figures like grandparents, uncles, educators, etc.) told me I am a winner, an intelligent guy, etc., I will tend to define myself, at an inner level, as being so. This is the first corner, the corner of I (or me). Who You (the other) are is often defined by what our parents believed about other parents or people. If my white parents judged other black parents in a racist or tolerant way, and if I am white, I will tend to see You, a black person, either in a racist or in a tolerant way. It’s again about models, unconscious ones. This is the corner of You. Who We (as a group) are is often defined by what our parents thought about the environment. If your parents thought that they are surrounded by stupid people and they were the smartest around, they will lay an erroneous (by generalization) foundation for our opinion about ourselves or the corner of We. Another easy example is when the family belongs to an ethnic group (Jewish people, for instance) or a professional group (doctors or lawyers or politicians, for instance). In the end, the 4th corner, called the Primal We, is about spirituality. For instance, if the parents were obsessed with esoteric practices, hyper-religious or, on the contrary, atheists, they will shape our philosophy accordingly.

So, what’s the practicality of knowing the deeper feelings balance model? For instance, when you see that a client fails to develop satisfying social connections (corner 2 in the classic balance model), you might want to ask yourself if the client is not plagued by a quasi-hypnotic unconscious suggestion from his parents (“You are a loner”, “You are nobody”, corner 1), or an unconscious interdiction in corner 2 (“We don’t befriend non-white people”) or corner 3 (“You can’t find sufficiently smart people to talk to these days”) or corner 4 (“They go see God, their imaginary friend”). I think you get the idea.

So, here they are, 3 ways of doing a good therapy session, using the 3 levels: the classic balance model, the debate of capacities and the more subtle emotional balance model. Using only these 3 sub-models and the reframing provided by the concept of positum, almost everyone can do some basic counselling, using, of course, some commons sense, and preferably having some self-knowledge about their own inner world. This is the backbone of positive psychotherapy. In a future article I will also cover something that acts like the skin: the protocol.